A two year, $4 million studyof 307 people, purporting to compare low carb to low fat diets has been completed, apparently showing similar weight loss after two years, but improved blood lipids for people who followed the low carbohydrate diet. They tell us study results show it doesn’t matter which way we diet. But the study has several problems:

A two year, $4 million studyof 307 people, purporting to compare low carb to low fat diets has been completed, apparently showing similar weight loss after two years, but improved blood lipids for people who followed the low carbohydrate diet. They tell us study results show it doesn’t matter which way we diet. But the study has several problems:

- The low carb diet went for 12 weeks, after which people were encouraged to add 5 grams of carbohydrates daily for a week, increasing carbohydrates until their weight stabilized.

- The low calorie diet went on for 2 years. So a short term diet was compared to a long term diet.

- No one looked at actual food intake. Yep, a diet study with no data on what people actually ate eventhough they kept food diaries.

- And data from dropouts was extrapolated and included, or as the rest of us call it, the data was made up.

Why Would You Include Data from Dropouts?

The last point may need some explanation. Usually one would compare only people who followed the protocol, but in recent years people wondered what happened to the dropouts. Why would you ever look at data from people who didn’t follow the diet? It seems counterintuitive, but there are legitimate questions here, if too many people drop out of a study it may be because the protocol causes real life problems. If you are looking at what is called “Intent to Treat” then you might well look at the end result to see if prescribing a certain course of action is likely to help in the real world where people don’t always follow directions. It tells you what people might do in an experimental context, not which course of action is better. But you want to use real end data on the dropouts, and to segregate it from the compliers. If you mix the data together, then it is impossible to tell whether Protocol A (say a low carbohydrate diet) is better than Protocol B (say, a low calorie diet) when people follow directions. In other words, you would never use Intent to Treat (ITT) in a comparison of which diet is actually better. An ITT analysis can draw the exact opposite conclusion to a traditional analysis. But the researchers did just that in this study.

“To assess departures from the missing-at random assumption under informative withdrawal-that is, the missing weights are informative for which patients chose to withdraw or continue to participate in the study-we present sensitivity analyses. As such, we assume that all participants who withdraw would follow first the maximum and then minimum patient trajectory of weight under the random intercept model.” (italics mine)

So they did not use real outcomes for the noncompliers or even assume that the real outcomes on the others would apply. They extrapolated them based upon a model that significantly understates the difference between the two groups. (They spent more time and charts on the model than on the real data, not all of which is reported in the full text study.) That means the data were made up based on the group that continued, not at the average rate, but at the “minimum trajectory”. In other words they extrapolated at the low end of the data, which minimizes the effectiveness of the diet. Consider that adding in the dropouts alone can make significant differences. Richard Feinman who has looked at Intent To Treatment gives the following table showing how ITT masks the true response of those that follow a low carb diet in two prior studies:

Weight Loss in Diet Comparisons and the Effect of Analysis. Data for 12 months Weight Loss (kg)

With Drop-outs SD Only Study Subjects SD

Foster, et al. low carb 4.4 6.7 7.3 7.3 low fat 2.5 6.3 4.5 7.9 difference 1.9 2.8

Stern, et al. low carb 5.1 8.7 7.3 8.3 low fat 3.1 8.4 3.7 7.7 difference 2 3.6

Feinman Nutrition & Metabolism 2009 6:1 doi:10.1186/1743-7075-6-1

Frank Hagensays “if you use the numbers that include the people who dropped out of the diet, in the “With Drop Outs” column, where the low carb group in the “Foster, et. al.” study only lost 1.9 kg more than the low fat group. But look at the column titled “Only Study Subjects”, comparing those that actually followed the low carb or low fat diet, and you find that the low carb dieters actually lost 2.8 kg [6 pounds] more than the low fat dieters (47% more weight). For the “Stern, et. al.” study, we find even greater numbers: a difference of 2 kg between the diets using ITT and 3.6 kg [8 pounds] when counting those that actually followed the diet plans. That’s 80% more weight loss.” As you can see, the difference in outcomes is quite a bit more distinct when dropouts are not included.

In this study, the authors did not segregate the data for only people who followed the diet. So we do not know what percentage of the low carbohydrate dieters were still on a low carbohydrate diet at the end nor what percentage were on a low calorie diet. Judging from the triglyceride rates which drop when carbohydrates are low, few of the final group of dieters were still on a low carbohydrate diet. This is confirmed by the higher level of urinary keytones at 3 and 6 but not 12 or 24 months. But that would happen anyway because of the design of the study.

Triglyceride Effects:

Diet Group 3 Mos. 6 Mos. 12 Mos. 24 Mos. Low Fat -17.99 -24.3 -17.92 -14.58 Low Carb -40.08 -40.06 -31.52 -12.19

What Is A Low Carbohydrate Diet?

Common sense would say that to compare two diets, one low carbohydrate and one low calorie, you need to have some sort of set criteria for what is eaten and to run both diets similarly. In the study, the low carb group had a very low carbohydrate induction phase followed by gradual increases of 5 grams daily each week, increasing indefinitely. The low fat group did not increase calories during this time. As the abstract says:

A low-carbohydrate diet, which consisted of limited carbohydrate intake (20 g/d for 3 months) in the form of low–glycemic index vegetables with unrestricted consumption of fat and protein. After 3 months, participants in the low-carbohydrate diet group increased their carbohydrate intake (5 g/d per wk) until a stable and desired weight was achieved. A low-fat diet consisted of limited energy intake (1200 to 1800 kcal/d; ≤30% calories from fat). Both diets were combined with comprehensive behavioral treatment.

Now if you are on a low carbohydrate diet for 12 weeks months, and then transition to a higher carbohydrate diet, with no outer level specified, then you are off of the low carbohydrate diet at 100 g daily by week 28 (or 6 months )and on a high carbohydrate diet of over 150 grams ten weeks after that. At 12 months, you’d be up to 210 grams per day which probably causes weight gain. So even those who followed the protocol were not on a low carbohydrate diet for most of the two years. We are comparing a low-calorie weight-loss diet that lasted for two years with a low-carb diet that reached maintenance level within 6 months.

The study suggested only continuing the additional carbohydrates “until desired weight was achieved” but since the average starting weight was 226 pounds, and average weight loss was 27 pounds at maximum, then “desired weight” was never achieved.

A better design would probably had the induction diet for two weeks, followed by a 60-80gram low carbohydrate diet for the entire period. This is the methodology used in the Atkins diet books which the researchers claim they were using.

And What Were The Results?

According to the study, “During the first 6 months, the low-carbohydrate diet group had greater reductions in diastolic blood pressure, triglyceride levels, and very-low-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels, lesser reductions in low-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels, … had greater increases in high-density lipoprotein [good] cholesterol levels.” The low carb group also had more adverse effects, primarily bad breath, constipation, and dry mouth during the first six months of the study which all could have been avoided with some simple counselling on which foods to eat.

Let us look at the results while participants were still on the low carb diet at 6 months:

Indicator Low Fat Low Carb

Weight loss 25 27 pounds

Triglycerides -24.3 -40.6

HDL +0.9 +6.2

TGL/HDL 2.15 1.39 (under 2 preferred)

As we can see, all parameters were better with a low carbohydrate diet at the 6 month period when carbohydrates had just reached maintenance levels. Curiously blood sugar was not tested although most participants are likely to suffer from Metabolic Syndrome (diabetics were excluded.) The advantage continued at 12 months although by that time carbohydrate levels were approaching the weight gain level and some of the weight gain was noted. By 2 years, only the gain in good cholesterol persisted, although in fact there was a “strong trend” to lower blood pressure in the formerly low carbohydrate group.

At the end of two years, while the low fat group was still dieting and the low carb group had been off their diet for a year, weight loss was the same (well there was slightly more weight loss in the low carb group but it wasn’t considered significant.) This should be news, although I admit the story is still muddled. It certainly doesn’t lead to the conclusion that the type of diet doesn’t matter though, as the researchers have been saying.

Ketones and Low Carbohydrate Diets

Why would they design a weight loss study this way? Tom Naughton looked up the papers the researchers had previously done, and found a bias for low fat diets in their previous research. I don’t necessarily suspect that they deliberately were seeking to waste $4 million or to mislead the public about diets. I think that the bias about a ketogenic diet’s safety and an imcomplete knowledge about how it works probably biased the study design. First off, the Atkins diet, upon which the low carb diet was ostensibly based, starts with an induction period (usually 2 weeks of an extremely low carb ketogenic diet) and then adds carbs gradually until just before the body stops producing ketones, somewhere between 60-80 grams for most people. It doesn’t add carbs forever.

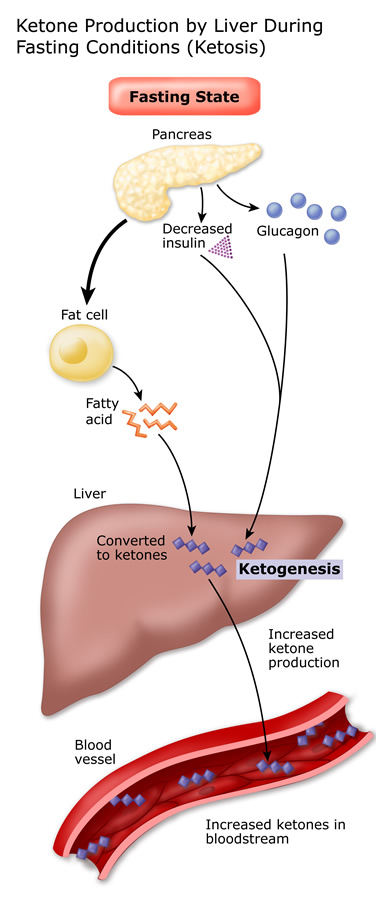

Ketones are normal byproducts of burning fat which are water (blood) soluble. These blood-soluble fats are a source of energy for tissues including the muscles, brain and heart. Ketones can significantly substitute for sugar in the brain. But both ketosis, a normal way of extracting energy from fat, and ketoacidosis, a dangerous condition where the body is breaking down its own tissues from starvation or Type 1 Diabetes, produce ketones. Ketones are easily measured but distinguishing the cause is not. So the presence of keytones seems to send off alarms even when the cause is benign. I have heard many doctors and nurses caution against ketosis in a low carb diet “just to be sure” when what was really dangerous would be ketoacidosis- ketosis is the point of most low carb diets because it indicates burning fat. This study did measure ketones, but didn’t distinguish between the causes, so treats the presence of ketones in the urine as potentially dangerous. This causes me to believe that the researchers wanted to limit the time spent in ketosis, and sloppily did not put an upper limit on carbohydrates. Unfortunately there is no discussion of the carbohydrate increase design in the study.

Low carbohydrate diets have been shown to increase weight loss in a number of studies including the current diet, the last Foster study and the Stern study discussed above, but their reporting has been often distorted because of the low fat bias in nutrition which has been in effect since Ancel Keys promulgated the lipid hypothesis based upon highly selected country data in 1963. For instance in the Farmington study, high fat diets were associated with lower rates of most cancers but the headlines and research summaries focused on the few, less common cancers that were associated with high fat diets. The researchers indicated that they wouldn’t have gotten funding for further analysis afterwards. (Atkins archives). A meta study (now withdrawn) by the Cochrane Group showed a weighted average of 5.1 vs 7.5 lbs at 12 months, but was reported as “no significant difference”. A 2006 study by vegan-proponent Neil Barnard showed that a low glycemic index, flourless, vegan diet, that had fewer carbs than the American Dietetic Diet, was healthier, but it was not described as lower carbohydrate or even low grain diet. The ADA diet has 6-11 servings of grains or starches a day plus fruits and vegetable sources of carbohydrates, giving approximately 220 g per day and allows unhealthy refined starches and vegetable oils (also avoided by the vegan group). Only now, since Gary Taube’s New York Times article What If It’s All Been a Big Fat Lie? blasted through the establishment anti-fat bias, have low carbohydrate diets been considered potentially allowable.

If you only look at weight loss, the differences between a low carbohydrate and low calorie diet are minimal unless the low carb diet is ketogenic, but the low carb diet has a slight advantage. If you look at overall health parameters including blood sugar, HDL, TGL and blood pressure, a low carb diet has distinct advantages. Based upon this study at every point there was no difference in bone loss. During an induction period there are significant side effects to a low carbohydrate diet for 7-16 days, including a dry mouth, bad breath, headache and constipation but these will pass after the sugar withdrawal symptoms pass- essentially you are coming off of a drug. Mineralization, lots of green vegetables and adequate hydration will help prevent this.

If you wish to learn more, including ways of transitioning with fewer side effects, I cannot suggest anything better than Paul Bergner’s course “Insulin Resistance: Pathophpysiology and Natural Therapeutics” which puts everything together with CDs and over a hundred pages of resource materials. (I have no financial interest in promoting this, but it is the best I have found.”)

Sources:

Eades, Michael. Metabolism and Ketosis

Foster, et. al. Weight and Metabolic Outcomes After 2 Years on a Low-Carbohydrate Versus Low-Fat Diet A Randomized Trial

Feinmann, Richard. Intent to Treat: What is the Question?

Hagen, Frank. Lies, Damn Lies and Statistics.

Howard BVet al.: Low-fat dietary pattern and weight change over 7 years: the Women’s Health Initiative Dietary Modification Trial.

Howard BV, et al.: Low-fat dietary pattern and risk of cardiovascular disease: the Women’s Health Initiative Randomized Controlled Dietary Modification Trial.

Naughton, Tom. Another Biased Study? Maybe…

Naughton, Tom. Inside Information from “Fat Throat”

Barnard, N. Diabetes Care, August 2006; vol 29: pp 1777-1783. News release, Physicians Committee for Responsible Medicine.

Cochrane Database. Advice on Low Fat Diets for Obesity.

Taube, Gary. What If It’s All Been A Big Fat Lie?

See Also:

What Does Research Say About Eating Meat?

Fructose, Sugar, Poison and Obesity

The China Study Misrepresents Data: Does Not Support a Vegan Diet.